| |

|

|

BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO |

|

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

is one of the most common etiologies of peripheral vertigo. As the name implies,

the cause of vertigo is benign. Despite being of a benign etiology, this entity

can produce severely disabling symptoms of vertigo, nausea and vomiting, and

often brings a patient to the emergency room. Fortunately, BPPV can be diagnosed

clinically by a simple bedside maneuver and can be treated successfully using

non-pharmacological means in most cases. |

|

Epidemiology

Mean age of onset – 54 years (range 11-84 yrs)

Incidence – about 107 / 100,000 / year

Of patients referred to a speciality dizziness

clinic: about 17% have BPPV |

|

Pathophysiology

BPPV is caused by loose particle debris of otoliths, also known as otoconia.

Otoliths are normally attached to a membrane inside the utricle and saccule.

There are composed of calcium carbonate particles. Since they are denser than

the surrounding endolymph, when they break free, gravity pulls them downward

into the posterior semicircular canals of the vestibular labyrinth.

Otoliths may become displaced from the utricle by aging,

head trauma, or labyrinthine

disease. When this occurs, the otoliths almost always enter the

posterior semicircular duct since this is the most dependent of the three ducts.

Changing head position relative to gravity causes the free otoliths to

gravitate longitudinally through the canal. The concurrent flow of endolymph

stimulates the hair cells of the affected semicircular canal, causing vertigo. |

|

|

Signs / Symptoms

•

Vertigo

Intermittent (paroxysmal)

Triggered by head movements (characteristically

occurs when rolling over in bed, leaning forward or turning the head

horizontally)

Usually lasts 10-20 seconds

•

Nystagmus

Fast phase will be toward the affected ear in BPPV

Mixed torsional and vertical components

Latency of a few seconds after provocative maneuver

•

Nausea, vomiting

Associated with vertigo |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), the most common

cause of peripheral vertigo is made by observing the response to a bedside test

called the “Dix-Hallpike Maneuver” as

demonstrated below. |

|

|

|

(Figure Above) The Dix–Hallpike Test of a

Patient with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo Affecting the Right Ear.

In Panel A, the examiner stands at the patient's right side and rotates the

patient's head 45 degrees to the right to align the right posterior semicircular

canal with the sagittal plane of the body.

In Panel B, the examiner moves the

patient, whose eyes are open, from the seated to the supine right-ear-down

position and then extends the patient's neck slightly so that the chin is

pointed slightly upward. The latency, duration, and direction of nystagmus, if

present, and the latency and duration of vertigo, if present, should be noted.

The red arrows in the inset depict the direction of nystagmus in patients with

typical benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The presumed location in the

labyrinth of the free-floating debris thought to cause the disorder is also

shown. Please note: this maneuver should not be performed in patients with

symptomatic cervical stenosis. Reproduced from Furman and Cass, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo,

NEJM Vol 341: 1590-1596,1999.

|

|

![]() |

(Above) Video of Nystagmus with BPPV [Place the cursor over the

box and the video will play]. This middle-aged woman

presented with a two week history of positional vertigo preceded by turning over

in bed onto the right side. Just prior to the onset of symptoms, she had

extensive dental work, lying fully recumbent in the dental chair for several

hours. On examination, when the right ear was placed in the dependent position

using the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, she developed a burst of nystagmus (shown in

this video). The nystagmus had slow phases directed downward with a torsional

component such that the poles of the eyes rotated toward the above (left) ear.

Correspondingly, the quick phases beat up and counter-clockwise (from the

examiner's vantage). The nystagmus appeared more vertical on left gaze and more

torsional on right gaze. This pattern of nystagmus is just as expected from

stimulation of the right posterior semicircular canal. The patient was relieved

of all symptoms following a particle repositioning maneuver. (Reproduced

with permission of the American Academy of Neurology).

|

The diagnostic criteria for BPPV are shown below:

|

|

|

Reproduced from Furman and Cass, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, NEJM. Vol

341: 1590-1596, 1999.

Treatment

The most effective treatment for BPPV is the Epley

Maneuver, with a success rate of about 80%. The purpose of this

maneuver is to reposition the loose endolymph crystals by a series of movement

which utilize changes in head position and the effect of gravity on the otoconia. |

|

|

|

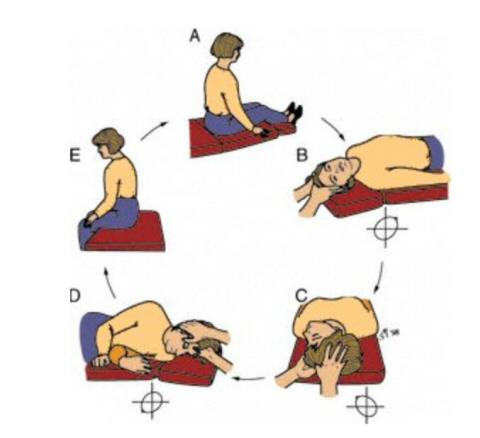

A) The patient starts upright

B) The patient leans backwards briskly

(with help of the clinician) and head turned 45 degrees so that the affected

ear, as previously determined by the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, is facing down

C) After the nystagmus stops (30-60

seconds) the patient is turned 90 degrees so that the opposite ear is now facing

down.

D) After about 30-60 seconds, the patient

turns the same direction into the lateral decubitus position so that nose faces

down

E) After about 30 seconds, the patient is

returned to the sitting position

The patient should be kept upright for the next 48 hours if possible, even

while sleeping. |

|

|

|