| |

|

|

COMMON ENTRAPMENT

NEUROPATHIES |

|

|

|

|

|

Median Neuropathy at the Wrist (Carpal Tunnel

Syndrome)

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common of all entrapment

neuropathies.

Anatomy

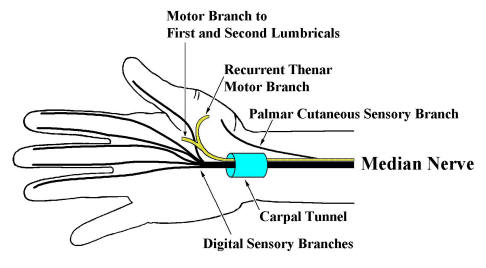

Just proximal to the wrist, the Palmar Cutaneous

Sensory branch leave the median nerve to run subcutaneously to supply

sensation over the thenar eminence. The median nerve then enters the wrist

through the carpal tunnel. Carpal bones make up the floor and sides of the

carpal tunnel, with the thick transverse carpal

ligament forming the roof. In addition to the median nerve, nine

flexor tendons traverse the carpal tunnel as well. In the palm, the median nerve

divides into motor and sensory divisions. The motor division travels distally

into the palm supplying the First and Second lumbricals. In addition, the Recurrent

Thenar Motor Branch is given off. This branch turns around (hence,

recurrent) to supply muscular branches to most of the thenar eminence including

the opponens pollicis, abductor pollicis brevis and superficial head of the

flexor pollicis brevis. The sensory fibers of the

median nerve that course though the carpal tunnel supply the medial thumb,

index, middle and lateral half of the ring finger.

|

|

|

|

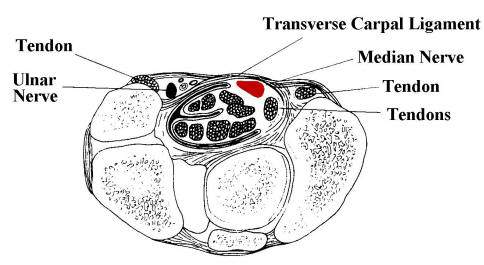

Above: cross sectional

anatomy through the wrist at the carpal tunnel (median nerve in red). |

|

Etiology

Most cases are idiopathic. In most cases, edema, vascular sclerosis and

fibrosis are seen, findings consistent with repeated stress to connective

tissue. Demyelination follows compression and ischemia of the median nerve, and

if severe enough, Wallerian degeneration and axonal loss ensue. Occupations or

activities which involve repetitive hand use clearly increase the risk of CTS.

Other predisposing etiologies include certain systemic disorders, most notably hypothyroidism,

rheumatoid arthritis and amyloidosis.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with CTS may present with a variety of symptoms and signs. Women are

more often affected than men. Although usually bilateral clinically and

electrically, the dominant hand is usually more severely affected, especially in

idiopathic cases. Patients complain of wrist and arm pain associated with

paresthesias in the hand. The pain may be localized to the wrist, or may radiate

to the forearm, arm or rarely the shoulder; the neck is not affected. Some

patients may describe a diffuse, poorly localized ache involving the entire arm.

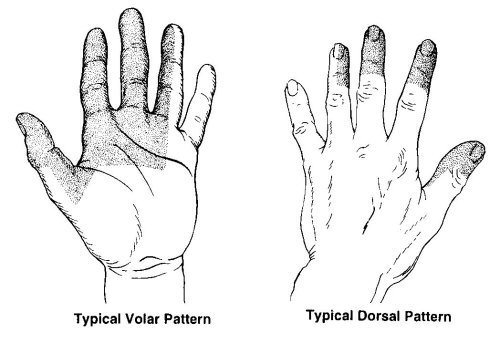

Paresthesias are frequently present in a median distribution (medial thumb,

index, middle and lateral ring finger). While many patients report that the

entire hand falls asleep, if asked directly about little finger involvement,

most will subsequently note that the little finger is spared.

|

|

|

|

Above: typical

distribution of sensory symptoms in carpal tunnel syndrome. |

|

Symptoms are often provoked when either a flexed or extended wrist posture is

assumed. Most commonly, this occurs during ordinary activities, such as driving,

holding a phone, book or newspaper. Nocturnal

paresthesias are particularly common. During sleep, persistent wrist

flexion or extension leads to increased carpal tunnel pressure, nerve ischemia

and subsequent paresthesias. Patients will frequently awaken from sleep and

shake or ring out their hands, or hold them under warm running water.

Sensory fibers are involved early in the majority of patients. Pain and

paresthesias usually bring patients to medical attention. Motor fibers may

become involved in more advanced cases. Weakness of thumb abduction and

opposition may develop, followed by frank atrophy of the thenar eminence. Some

patients describe difficulty buttoning shirts, opening a jar, or turning a

doorknob. However, it is unusual to develop significant functional impairment

from loss of median motor function in the hand.

The sensory examination may disclose hypesthesia in the median distribution.

Sensation over the thenar area in spared, as this area is innervated by the

Palmar Cutaneous Sensory Branch, arising proximal to the carpal tunnel. The Tinel's

sign, tested by tapping over the median nerve at the wrist, and the Phalen's

maneuver, holding the wrist passively flexed, may both provoke

symptoms.

The motor examination involves inspection of the hand looking for wasting of

the thenar eminence (severe cases) and testing the strength of thumb abduction

and opposition.

|

|

|

|

Ulnar Neuropathy at the Elbow

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (UNE) is second only to

median nerve entrapment at the wrist (i.e., carpal tunnel syndrome) as the most

common entrapment neuropathy affecting the upper extremity. Lesions of the lower

brachial plexus or C8-T1 roots may result in similar symptoms to UNE.

Anatomy

The ulnar nerve is essentially derived from the C8

and T1 roots. All ulnar fibers travel through the lower

trunk of the brachial plexus and then continue into the medial

cord. The terminal extension of the medial cord becomes the ulnar

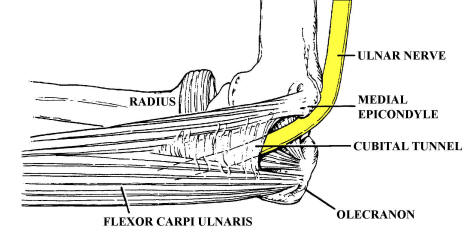

nerve. The ulnar nerve then travels medially and distally toward the elbow. At

the elbow, the nerve enters the ulnar groove

formed between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon process. Slightly distal

to the groove in the proximal forearm, the ulnar nerve travels under the

tendinous arch of the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle, known as the

humeral-ulnar aponeurosis (HUA) or "cubital

tunnel." Muscular branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris and the

medial division (fourth and fifth digits) of the flexor digitorum profundus are

then given off.

The nerve then descends through the medial forearm, giving off no further

muscular branches until after the wrist. Slightly proximal to the wrist, the

dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory branch exits to supply sensation to the dorsal

medial hand and the dorsal fifth and medial fourth digits. The nerve next enters

the medial wrist to supply sensation to the volar fifth and medial fourth digits

and muscular innervation to the hypothenar muscles, the palmar and dorsal

interossei, the third and fourth lumbricals, and two muscles in the thenar

eminence, the adductor pollicis and the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis.

|

|

Etiology

UNE usually occurs as a result of chronic mechanical compression or stretch,

either at the groove or at the cubital

tunnel. Although rare cases of ulnar neuropathy at the groove are

caused by ganglia, tumors, fibrous bands, or accessory muscles, most

are caused by external compression and repeated trauma. Elbow

fracture, often years before, and subsequent arthritic change of the elbow joint

may result in so-called tardy ulnar palsy.

In addition, chronic minor trauma and compression (including leaning on the

elbow) can either exacerbate or cause ulnar neuropathy at the groove. Ulnar

neuropathy at the groove is also common in patients who have been immobilized

because of surgery or who sustain compression during anesthesia or coma.

Distal to the groove is the cubital tunnel,

the other major site of compression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the

elbow. Although some use the term cubital tunnel syndrome to refer to all

lesions of the ulnar nerve around the elbow, it more properly denotes

compression of the ulnar nerve under the HUA. Some individuals have congenitally

tight cubital tunnels that predispose them to compression. Repeated

and persistent flexion stretches the ulnar nerve and increases the

pressure in the cubital tunnel, leading to subsequent ulnar neuropathy.

|

|

Clinical Presentation

UNE caused by compression at the groove or at the cubital tunnel may present

in a similar manner. In contrast to carpal tunnel syndrome in which sensory

symptoms predominate, motor symptoms are more common in ulnar neuropathy,

especially in chronic cases. In some patients, insidious motor loss may occur

without sensory symptoms, particularly in those with slowly worsening mechanical

compression. As most of the intrinsic hand muscles are ulnar innervated,

weakness of these muscles leads to loss of dexterity and to decreased grip and

pinch strength. These are often the complaints that bring the patient to medical

attention. There may be atrophy of both the hypothenar and thenar eminences (the

ulnar-innervated adductor pollicis and deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis

are in the thenar eminence). However, thumb abduction is spared (median and

radial innervated).

|

|

|

|

In moderate or advanced cases, examination often shows the classic hand

postures that occur with ulnar muscle weakness. The most recognized is the "Benediction

posture" (see photo above). The ring and little fingers are clawed, with the metacarpophalangeal joints hyperextended and the proximal and distal

interphalangeal joints flexed (from third and fourth lumbrical weakness), while

the fingers and thumb are held slightly abducted (from interossei and adductor

pollicis weakness). Patients with ulnar neuropathy may not be able to flex the

distal fourth and fifth fingers completely when making a grip; in contrast, the

median-innervated second and third distal digits flex normally.

In UNE, sensory disturbance, when present, involves the volar and dorsal

fifth and medial fourth digits, and the medial hand. The sensory disturbance

does not extend proximally much beyond the wrist crease. Sensory involvement

extending into the medial forearm implies a higher lesion in the plexus or nerve

roots (i.e., this is the territory of the medial antebrachial cutaneous sensory

nerve, which arises directly from the medial cord of the brachial plexus).

Pain, when present, may localize to the elbow or radiate down to the medial

forearm and wrist. Paresthesias may be reproduced by placing the elbow in a

flexed position or by applying pressure to the groove behind the medial

epicondyle. The ulnar nerve may be palpably enlarged and tender. Especially in

patients with ulnar neuropathy at the cubital tunnel, the nerve may be palpably

taut with decreased mobility.

|

|

|

|

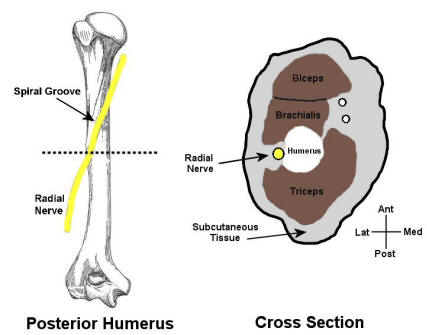

Radial Neuropathy at the Spiral Groove

Of the major upper extremity nerves, compression of the

radial nerve is less common. However, the radial nerve is susceptible to

external compression and can result in a classic syndrome of wrist and finger

drop.

Anatomy

The radial nerve receives innervation from all three

trunks of the brachial plexus and, correspondingly, a contribution from each of

the C5-T1 nerve roots. After each trunk divides into an anterior and posterior

division, the posterior divisions from all three trunks unite to form the

posterior cord. The posterior cord

gives off the axillary, thoracodorsal, and subscapular nerves before becoming

the radial nerve. In the high arm, the radial nerve first supplies the three

heads of the triceps brachia before wrapping around the posterior hummers in the

spiral groove.

Descending into the region of the elbow, muscular branches are then given off to

the brachioradialis, and then all the extensors of the wrist and fingers. In

addition, the superficial radial sensory nerve is given off to supply sensation

over the lateral dorsum of the hand as well as part of the thumb and the dorsal

proximal phalanges of the index, middle, and ring fingers.

Etiology

The most common radial neuropathy occurs at the spiral groove. Here, the

nerve lies juxtaposed to the hummers and is quite susceptible to compression,

especially following prolonged immobilization (see figure above). One of the

times this characteristically occurs is when a person has draped an arm over a

chair or bench during a deep sleep or while intoxicated ("Saturday

night palsy"). The subsequent prolonged immobility results in

compression and demyelination of the radial nerve.

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, marked wrist drop and finger drop develop in radial neuropathy at

the spiral groove. Notably, elbow extension (triceps) is spared. Sensory

disturbance is present in the distribution of the superficial radial sensory

nerve, consisting of altered sensation over the lateral dorsum of the hand, part

of the thumb, and the dorsal proximal phalanges of the index, middle, and ring

fingers.

|

|

|

|

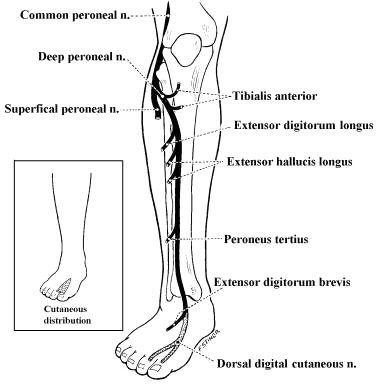

Personal Neuropathy at the Fibular Neck

Peroneal neuropathy often occurs from compression at

the fibular neck, where the nerve is quite superficial and vulnerable to injury.

Patients usually present with a footdrop and sensory disturbance over the

lateral calf and dorsum of the foot. However, patients with sciatic neuropathy,

lumbosacral plexopathy, or L5 radiculopathy may present with a similar pattern

of numbness and weakness.

Anatomy

The peroneal nerve is derived predominantly from the L4-S1 nerve roots, which

travel through the lumbosacral plexus and eventually the sciatic nerve. Within

the sciatic nerve, the fibers that eventually form the common

peroneal nerve run separately from those that distally become the

tibial nerve. The sciatic nerve bifurcates above the popliteal fossa into the

common peroneal and tibial nerves. The common peroneal nerve winds around the

fibular neck and passes through the fibular tunnel between the peroneus longus

muscle and the fibula. The common peroneal nerve then divides into superficial

and deep branches. The deep peroneal nerve

innervates the dorsiflexors of the ankle and toes. It also supplies sensation to

the web space between the first and second toes. The superficial

peroneal nerve innervates the ankle evertors and then supplies

sensation to the mid- and lower lateral calf.

Etiology

Peroneal neuropathy can be seen as a result of a variety of conditions. Acute

peroneal neuropathy often follows trauma, forcible

stretch injury, or compression from

prolonged immobilization. In the hospital, this occurs most often

postoperatively in patients who have received anesthesia or heavy sedation.

Slowly progressive lesions often suggest a mass lesion, such as a ganglion or

nerve sheath tumor. Entrapment of the peroneal nerve at the fibular tunnel,

although quite uncommon, may also present in a progressive manner.

Several other circumstances predispose one to peroneal neuropathy. Habitual

leg crossing may repetitively injure the peroneal nerve at the

fibular neck, where it is quite superficial. Similarly, repetitive

stretch from squatting, for example, by gardeners has also been

associated with peroneal neuropathy. In addition, patients who are thin or who

have recently lost a substantial amount of weight

may be prone to peroneal palsy, probably because of the lack of protective

supporting adipose tissue at the fibular neck.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with peroneal neuropathy at the fibular neck present with a

characteristic neurologic picture. Most often, both the deep and superficial

peroneal nerves are affected. Involvement of the deep peroneal nerve leads to

weakness of toe and ankle dorsiflexion, resulting in a foot

and toe drop. Dysfunction of the superficial peroneal nerve results

in weakness of foot eversion. Clinically, weakness of these muscles results in a

stereotyped set of symptoms. Patients note a slapping quality of their foot as

it hits the ground while walking. Weakness of eversion leads to a tendency to

trip, especially on uneven sidewalks or curbs, and an increased risk of sprained

ankles. When observed while walking, patients have a so-called "steppage

gait" whereby they bring their knee up higher than usual so that

the dropped foot clears the floor.

Sensory disturbance develops over the mid- and lower lateral calf and the

dorsum of the foot. Local pain and a Tinel's sign may be present over the

lateral fibular neck. In isolated peroneal neuropathy at the fibular neck,

function of the sciatic, tibial, and sural nerves remains normal. Most

important, ankle inversion is spared, mediated by the tibialis posterior (L5,

sciatic-tibial nerve). Finally, all reflexes, including the ankle reflex, remain

normal in an isolated peroneal neuropathy.

It is important to note that lesions of the sciatic nerve, lesions of the

lumbosacral plexus, and L5 radiculopathy may also present with a footdrop and

numbness over the lateral calf and dorsum of the foot. Indeed, these lesions,

especially early on, occasionally mimic a peroneal palsy almost exactly,

including abnormalities of sensation. It is in these cases that EMG studies are

especially helpful.

|

|

|

|

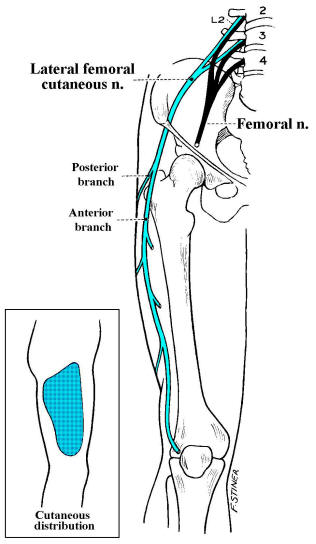

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Sensory Neuropathy (Meralgia

Paresthetica)

Entrapment of the lateral femoral cutaneous sensory

nerve is the most common entrapment neuropathy in the lower extremity. It is

associated with a classic clinical syndrome, known as meralgia

paresthetica.

Anatomy

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is a pure sensory nerve that is derived

from the L2-L3 roots and runs under the inguinal

ligament near the superior iliac spine, where it may be injured or

entrapped. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve only supplies sensation to a

large oval area of skin over the lateral and anterior thigh.

Etiology

This entrapment is more common in patients who are obese,

wear tight underwear or pants, or who have diabetes.

Although the vast majority of cases are due to an entrapment at the inguinal

ligament, rare cases have resulted from tumors and other mass lesions

compressing the upper lumbar plexus more proximally.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical syndrome, known as meralgia

paresthetica, results in a painful, burning, numb patch of skin over

the anterior and lateral thigh, sometimes worst in the standing position.

Because there is no muscular innervation from this nerve, there is no associated

muscle atrophy, weakness, or loss of reflexes. |

|

|

|