|

RECOGNITION OF SPONTANEOUS

CAROTID OR VERTEBRAL ARTERY DISSECTION |

|

Although generally rare, dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries

comprises a substantial number of

strokes among young adults and middle-aged patients.

The recognition of a spontaneous carotid or vertebral dissection requires a high

degree of clinical suspicion and an ability to recognize some key neurological

signs which help to hone in on the diagnosis. Dissection is critical to detect

before ischemia occurs so that treatment can be initiated promptly.

Arterial dissection occurs due to a tear in the intimal layer of the artery. The

tear allows blood to enter the wall and form an intramural hematoma. Depending

on which layer of the blood vessel is involved, either a subintimal or a

subadventitial hematoma develops. A subintimal hematoma tends to cause stenosis

of the artery, whereas a subadventitial hematoma often results in aneurysmal

dilatation of the artery. In the case of stenosis, sluggish blood flow distal to

the dissection results in the formation of fibrin clot. The clot continues to

enlarge and eventually breaks off to travel and dislodge downstream as an

embolus.

|

|

|

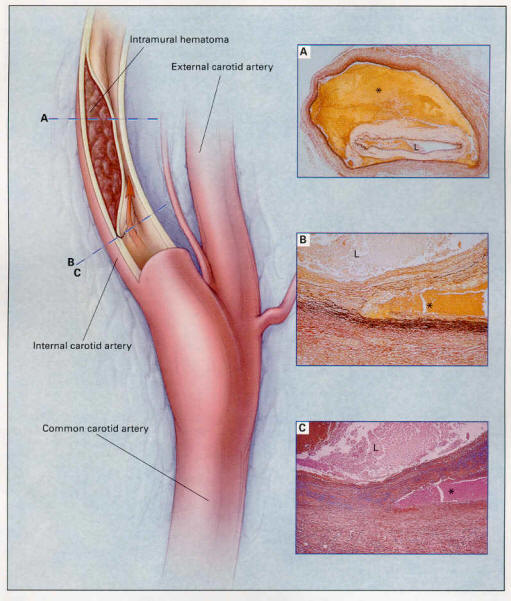

Above Figure: Pathological Findings in a

37-Year-Old Woman with a Dissection of the Internal Carotid Artery.

Photomicrographs of the right extracranial internal carotid artery (Panels A, B,

and C) show a dissection within the outer layers of the tunica media, resulting

in stenosis of the arterial lumen (L). The rectangles outlined in blue on the

left indicate the sites of the photomicrographs. The intramural hemorrhage

(asterisk) extends almost entirely around the artery (Panel A) (van Gieson's

stain, x4). Higher-power views of the internal carotid artery at the point of

dissection show fragmentation of elastic tissue (Panel B) (van Gieson's stain,

x25), with the accumulation of pale ground-glass substance in the tunica media,

indicated by the blue-staining mucopolysaccharides (Panel C) (Alcian blue, x25).

These changes are consistent with a diagnosis of cystic medial necrosis. From

Schievink et. al, Current Concepts: Spontaneous Dissection of the Carotid and

Vertebral Arteries, NEJM, 344 (12): 898, Figure 1, March 22, 2001.

|

|

Etiology

Most dissections involve some type of trauma or stretch to the head or neck

Sometimes, the trauma is trivial and forgotten by the patient

Higher incidence in certain congenital connective tissues disorders,

including Marfan's syndrome, cystic medial necrosis, and fibromuscular dysplasia.

|

|

Carotid Artery Dissection: Symptoms and Signs

The classic symptoms and signs of carotid dissection include the following:

• Pain or headache on one side of the head, face

or neck.

Headache (60-75%)

Usually unilateral

frontotemporal area

Of the patients with headache,

it is the initial symptom is 47%

Headache is described as severe

in 75%; mild-to-moderate in 25%

Headache onset is gradual in

85%; acute in 15% (and can mimic the presentation of SAH)

• Unilateral neck pain (25%), usually upper

anterolateral cervical region |

|

|

|

• Partial Horner’s syndrome (58%). Patients

develop ptosis and miosis (see figure above) as the sympathetic fibers to the

eye runs in the carotid sheath.

• Pulsatile tinnitus (27%)

• Cranial nerve palsies (12%), usually IX to XII;

impaired taste in 10%

• Cerebral or retinal ischemia

Cerebral hemispheric stroke or

TIA in the anterior circulation or

retinal ischemic symptoms (50-95%)

Transient monocular blindness

(25%)

TIA or transient monocular

blindness preceding stroke in 10-50% |

Vertebral Artery Dissection: Symptoms and Signs

Typically presents with the following:

• Pain in the back of neck, although can be

diffuse or frontal. Median interval between neck pain and ischemic symptoms is 2

weeks.

• Headache (median interval from onset of

headache to ischemia is 15 hours)

Headache occurs in 66%, usually

ipsilateral to dissection, and located in the occipital or frontal areas

Pain in back of neck (50%)

• Ischemia of

the posterior circulation (>90%).

Brainstem signs

Wallenberg’s syndrome |

Evaluation

Once the diagnosis of dissection is suspected,

fat-suppression MRI is the imaging study of choice. Intramural blood

can be well demonstrated on these scans. Routine Magnetic resonance angiography

(MRA) will often demonstrate narrowing or occlusion of the vessel, but in most

cases cannot differentiate dissection from other etiologies. |

|

|

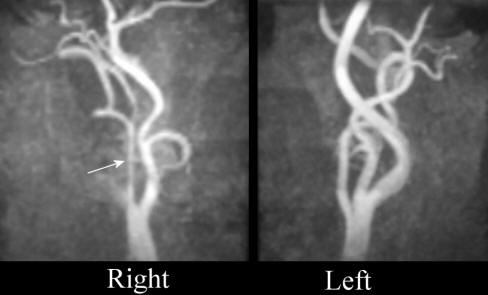

Above: Magnetic Resonance Angiogram - Both

Carotid Arteries - note the "string sign" of the right internal carotid,

compared to the normal image of the left internal carotid artery. Although not

specific for dissection, this pattern is highly suggestive

|

|

|

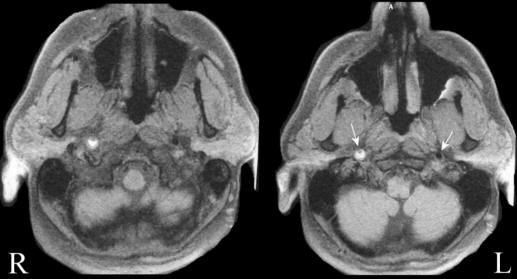

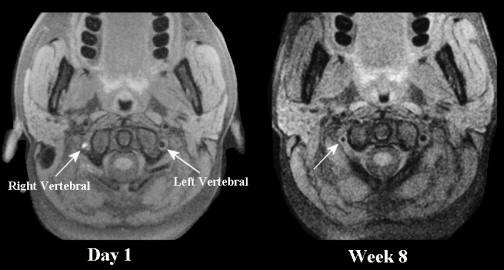

Above: MRI - Axial images of the lower

brainstem - fat suppression images (i.e., dissection protocol) - notice the

normal flow void (black signal in the left internal artery) and the bright

signal surrounding the right internal carotid area with a small lumen inside.

The bright signal is blood, indicating a dissection of the carotid artery.

|

|

|

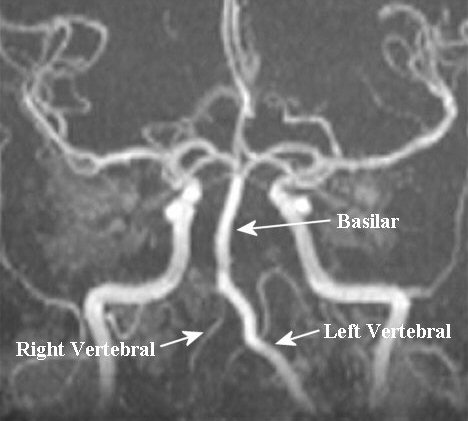

Above: Magnetic resonance angiogram of the

posterior circulation. Note the normal caliber of the left vertebral and basilar

arteries. However, the right vertebral is poorly seen, only a small amount of

flow is seen. This picture could result from a congenital hypoplastic vertebral

or from a dissection and a subsequent "string sign".

|

|

|

Above: Axial MRI imaging with fat

suppression (i.e., dissection protocol). Notice the normal flow void in the left

vertebral artery. However, the right vertebral artery is poorly seen. The area

of bright signal represents blood inside the vessel wall from the dissection.

|