| |

|

|

EXTERNAL COMPRESSION OF THE

SPINAL CORD |

|

|

|

|

Lesions that compress the spinal cord from an outside location are among the

most important and sometimes the most difficult to diagnosis. Extrinsic

compressive lesions often disrupt the motor and sensory roots at the level of the

lesion. This results in a lower motor neuron syndrome at the level of the lesion

(i.e., a radiculopathy).

|

|

|

|

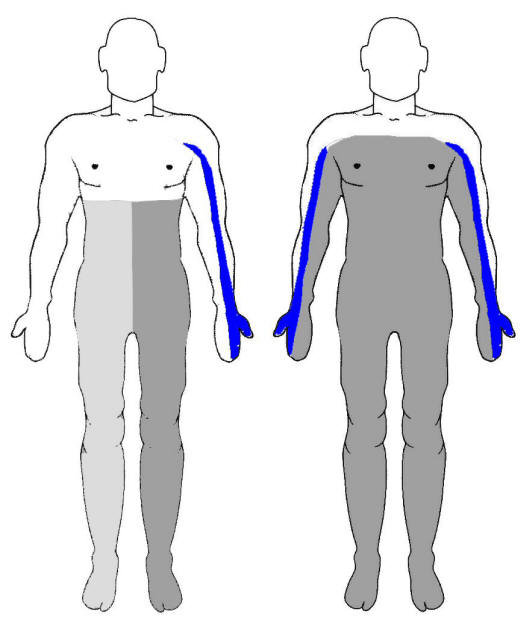

External lesions that compress the spinal cord produce symptoms in the

most superficial fibers of the long pathways first. Owing to the

specific lamination of the corticospinal and spinothalamic tracts

(lower extremity fibers most superficial and upper extremity fibers

deepest), cervical compressive lesions may cause sensory and motor symptoms to

appear first in the lower extremities. Thus, a common early pattern is a

radiculopathy at the level of the compression along with sensory and motor

symptoms in the distal lower extremities (see figure above - left: (blue)

radicular symptoms; (dark gray) spinal cord symptoms). Symptoms may then appear to "ascend" as

the compression becomes more severe and more deeply situated fibers are

successively affected. This anatomical arrangement is notorious for the

production of falsely localizing levels. For example, a distinct level of sensory

loss may be discernible at the level of the umbilicus (T10) in the case of a

compressive tumor at the mid-cervical region (see figure above - right). The unwary clinician obtaining a

magnetic resonance imaging scan of the thoracic cord might be falsely reassured

by a normal result because the level of the spinal cord where the lesion is

located is not imaged.

Therefore, the level of a sensory deficit found on

examination produced by extrinsic, compressive cord lesions only marks the

lowest possible level of the lesion; the actual pathology may lie anywhere

between the level of sensory loss and the foramen magnum. Identification of a

root level can be a very helpful sign; the upper limits of a sensory (or motor)

level found on examination only marks the lowest possible location of the lesion

in the spinal cord for the reasons described above. When, in addition, a focus

of back pain is present or distinct lower motor neuron signs are found at a

specific level, the level of the lesion may be pinpointed. Likewise, localized

pain or tenderness over a vertebral spinous

process may help localize a process associated with a destructive bony lesion. |

|

|

|

Lateral compressive lesions, though not causing a spinal cord hemisection per

se, may resemble the Brown-Séquard syndrome in presentation

(see figure above left). Except in the case

of early lesions, there is often some bilaterality to signs and symptoms with

lateral compressive lesions of the cord, especially when the contralateral cord

becomes compressed against the opposite side of the spinal canal. In cases of

lateral compression rather than hemisection, the half of the spinal cord

ipsilateral to the compressive lesion is usually more symptomatic than the

contralateral half. In the late stage of external spinal cord compression, the

syndrome evolves into a complete transection

with upper motor neuron paralysis and numbness below the lesion, and a segmental

lower motor neuron syndrome at the level of the lesion (see figure above -

right). |

|

|

|